On Thursday night, 35-year-old Sara took to the streets of Tehran for the first time in three years to protest against the Islamic Republic.

In late 2022, she’d been part of an uprising against Iranian authorities’ violent enforcement of female dress codes that ended with important government concessions but no change to the law. It feels different this time, she said, because Tehran’s Grand Bazaar — a symbol of conservative support for the government — has been on strike for nearly two weeks, emboldening others to join what’s become the greatest challenge in a generation to a regime that’s arguably weaker than ever before.

“It’s no longer about hunger or about food, it’s beyond that,” said Sara late on Thursday, hours before authorities blocked the internet. “People are out everywhere, small towns and places in Iran that I’ve never even heard of.”

The latest unrest to grip Iran began on Dec. 28 with traders in the labyrinthine bazaar protesting the government’s failure to manage a currency crisis that’s seen inflation skyrocket, leaving many of its 90 million citizens unable to afford even basic goods. It’s since spread to every corner of the country.

From Mashhad in the northeast to Abadan in the southwest, Iranians are revolting against a system that has isolated them from the world, shattered their economy, poured billions into hazardous regional policies and prioritized a nuclear program that ultimately led to Israeli-US airstrikes last summer.

The government response so far has been to offer a $7 monthly cash handout and a promise to curb price gouging and the exploitation of an exchange-rate system by wealthy, well-connected elites. But it feels to many like a paltry effort in the face of the sheer breadth of crises at hand.

“It’s as though there’s no government at work,” said Saeed Laylaz, former economic adviser to reformist former President Mohammad Khatami. “It appears that everything has been consigned over to fate and events — there’s no proper decision-making.”

Unverified videos posted to social media late on Thursday appeared to show hundreds of people gathered at major intersections and thoroughfares of Tehran. Others show large crowds cheering as a branch of the state broadcaster in the central city of Isfahan was set ablaze.

In a sign of how widespread the anger is, Reza Pahlavi — the exiled son of the Shah of Iran who was deposed in the 1979 revolution — has emerged as a unifying figure in the absence of any credible alternatives. He’s been both ridiculed and exalted but his statements supporting protesters appear to have brought them more momentum. He’s urged people to return to the streets on Friday night too.

“I’m not interested in him and neither are a lot of my friends, but the point is that no one really cares anymore — removing the current system is more important,” Sara said, adding that she heard people chanting “Long live the Shah” outside her windows most evenings this week. Sara, like others quoted in this story, declined to give her full name for fear of government reprisals.

The Pahlavi family was ousted in an Islamist uprising that was an angry rebuke of a modernizing but autocratic monarchy. Yet the Islamic Republic emerged as just as authoritarian, with a religious constitution that dramatically curtailed minority and women’s rights, persecuting thousands. A cold war with the US, mass executions and a long conflict with Iraq set the tone for the next few decades.

Successive rounds of protests that have grown bigger and more deadly since the 2019 gasoline riots have tested people’s patience with the government, whose response has always been to double down and quell unrest through fear and violence — including a surge in executions — rather than deliver any meaningful reform.

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps signaled on Friday that it’s likely to do the same this time around, and a Tehran prosecutor had earlier warned “rioters” who damage public property would face the death penalty.

“The continuation of this situation is unacceptable, and the blood of the victims of the recent terrorist incidents is on the necks of its designers,” the IRGC said in a statement, according to the semi-official Tasnim news agency.

Still, demonstrators have said the security forces aren’t as numerous this time compared with previous protests, potentially a sign that the regime doesn’t want to invite more anger, especially at such a perilous time for Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Iran’s security and defense doctrine, which defined geopolitics in the Middle East for decades, has been hobbled since Israel heavily bombed its armed allies Hezbollah and Hamas. Syria’s former President Bashar al Assad fled the country, ending an alliance that was critical to Tehran’s sphere of influence in the region.

Israel’s June war on Iran, which culminated in the US bombing key nuclear facilities, has left its leaders on edge over the possibility of further attacks. US President Donald Trump on Thursday repeated his recent threats against the regime.

On the first day of the protests, Sara was working in an office downtown, close to the bazaar. She said the gold traders were the first to shutter their shops and pour into the surrounding streets.

“The price of gold suddenly shot up, and they were refusing to sell and buy,” she said. It was just the latest in a long series of blows the country’s economy has suffered.

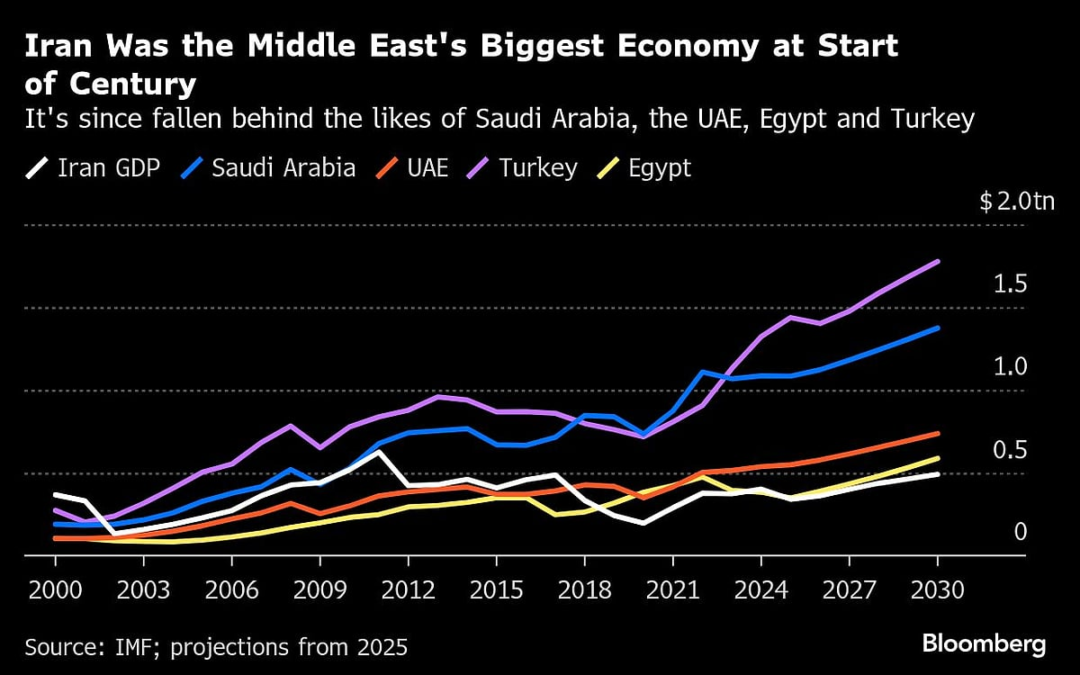

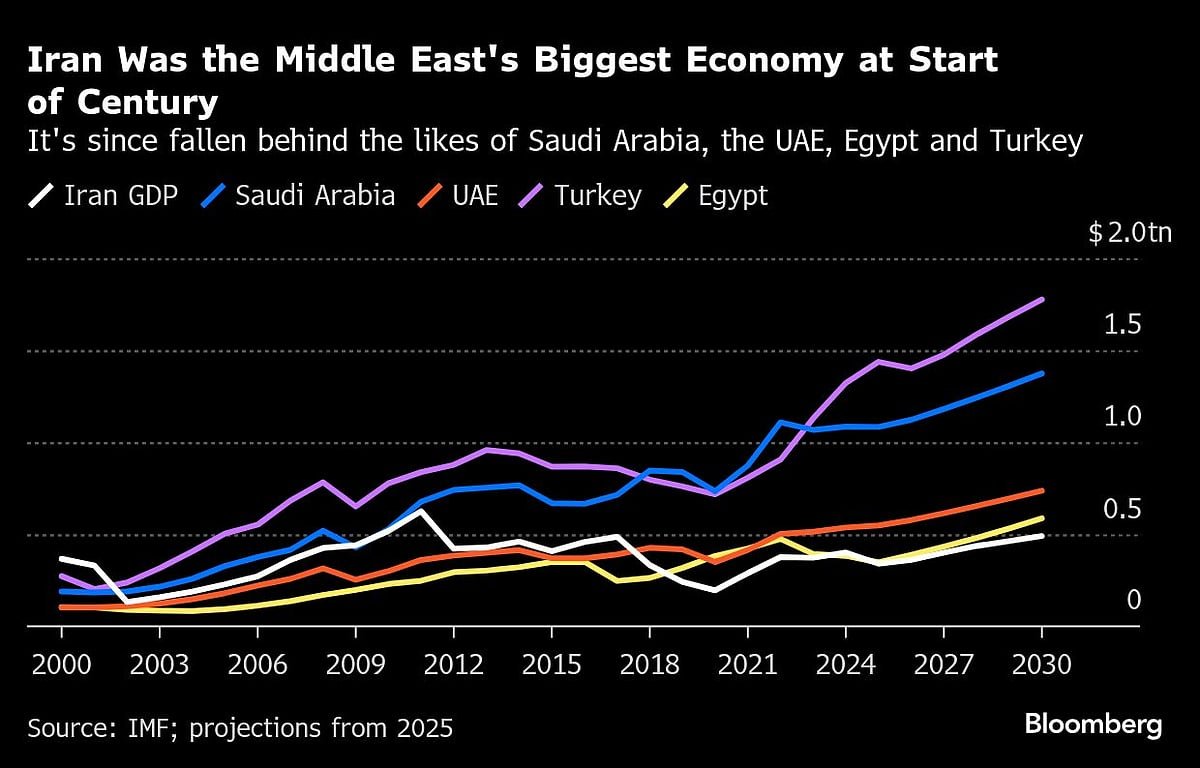

Iranian oil exports have dropped dramatically over the past decade as a result of tough US sanctions, its currency has plummeted to a record low and the country is desperate for investment in critical infrastructure. The economy has severely lagged its counterparts across the Middle East, and the recent fall in oil prices has exacerbated its problems.

In the year to June, the price of basic household items like chicken and bread soared 53% on average, according to the Statistical Center of Iran. In the month after Israel’s bombing campaign alone, there was a 10-30% spike in the prices of staples like rice, powdered milk and dairy products, the SCI said in a July report. According to Laylaz, in the past five years, 20 million households in Iran have been pushed into poverty.

“I’m part of the middle class, when even I balk at the price of a box of eggs I can’t imagine how bad it is for poorer families and working class households,” Sara said. “It’s a combination of ordinary people who have nothing left at all and the bazaaris who see they are going to lose whatever they have.”

Payam, who runs a small marketing and publishing company, has also taken part in major protests over the years.

“We haven’t seen anything like this before — when the very heart of the bazaar and the whole of Nasser Khosrow street is shuttered, then it’s certainly the most serious rebuke to the political system that I’ve seen,” Payam said, referring to a major trading thoroughfare that leads to the market. “And it’s not factional or political.”

Iran’s economic woes have in recent months been compounded by a water crisis driven by mismanagement, unchecked industrial growth and ground-water extraction. Scheduled power cuts have become a normal feature of life in a country with some of the biggest hydrocarbon reserves on earth.

In the face of so many existential and immediate challenges, officials are increasingly frank about their own limits.

“We’re stuck and we’re stuck in a bad way. From the day that we started, it’s just been one disaster after another and it doesn’t seem to stop,” President Masoud Pezeshkian told a cabinet meeting in July.

In recent days, Pezeshkian has sought to strike a sympathetic tone, urging security forces not to target “peaceful demonstrators.” In the first few days of the protests, he said people were right to be upset with the economic situation.

But the government’s words are beginning to ring meaningless for many.

“Now the single issue is death to the regime and the dictator,” said 53-year-old Zahra, who works in advertising.

“It’s even pointless to talk about how expensive things are or the economy,” she added. “People have had enough — they just want them to go.”

. Read more on World by NDTV Profit.