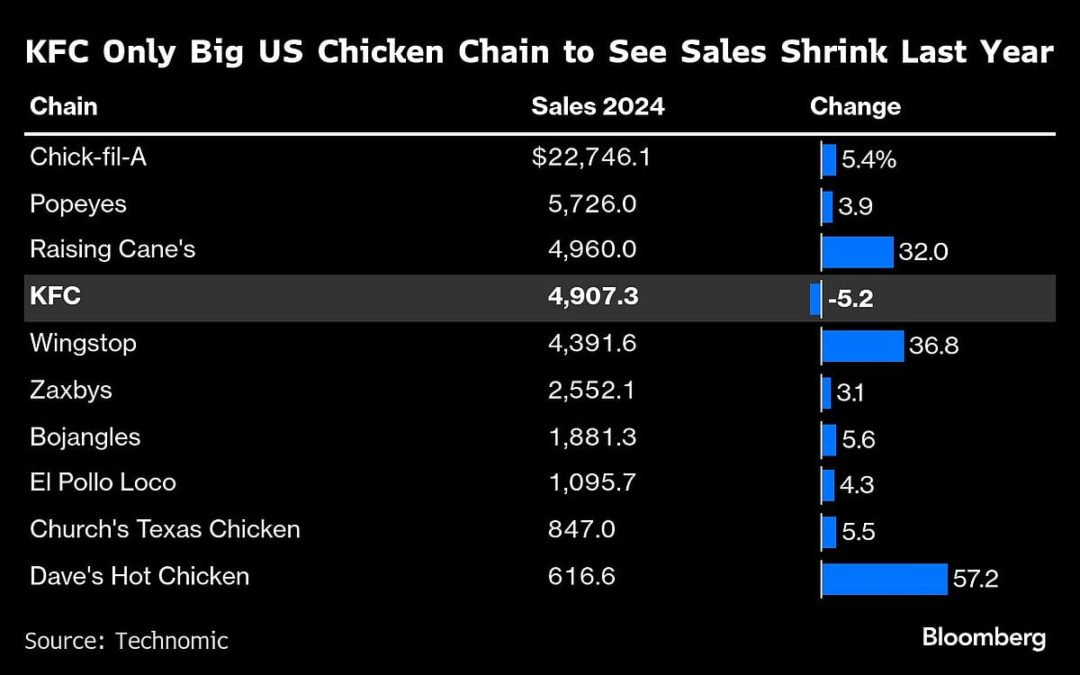

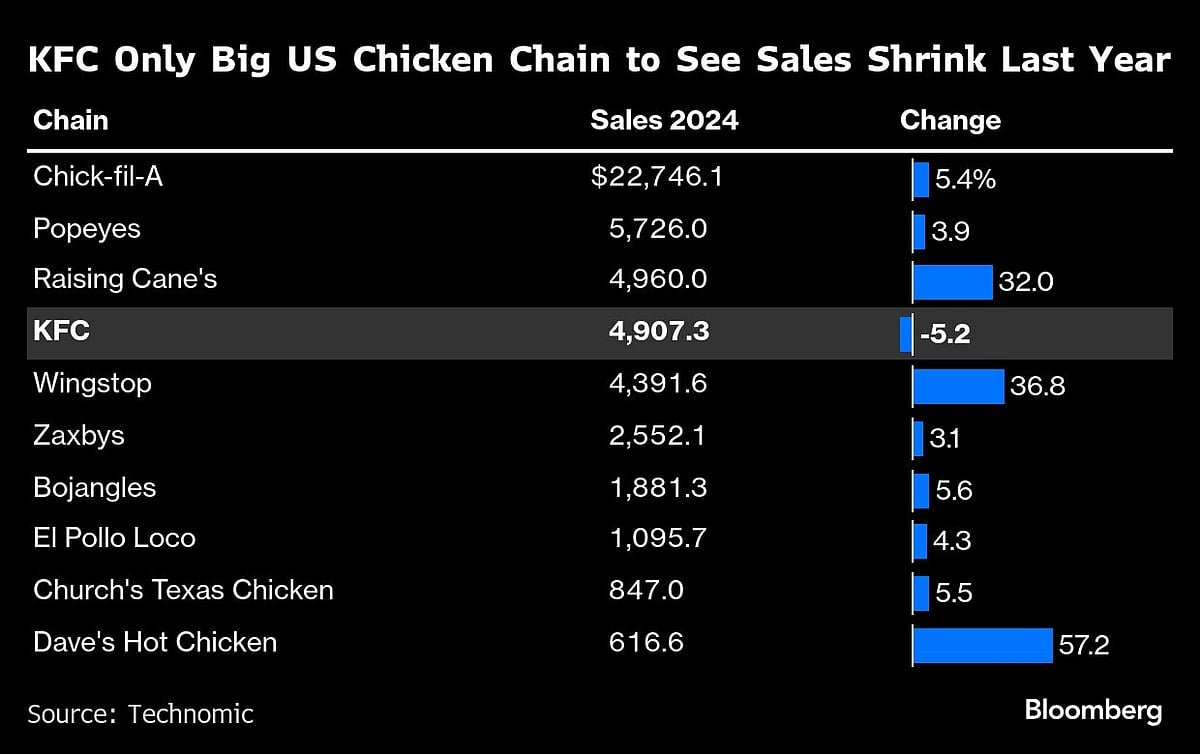

Fried chicken is making American restaurants more money than ever, except at KFC — the very place that pioneered selling it by the bucket load across the country.

Chick-fil-A fans swarm to its sandwiches and milkshakes, Popeyes’s launches go viral on social media, Raising Cane’s is drawing diners with its yellow Labrador mascot and 2.3 million TikTok followers, and McDonald’s now sells about as much chicken as it does beef.

But KFC? “Invisible” and “irrelevant,” according to one of its leaders. It was the only major chicken chain where sales fell last year.

“We used to be an American icon,” KFC US President Catherine Tan-Gillespie said in an interview. “Somewhere along the way we stopped acting like one.”

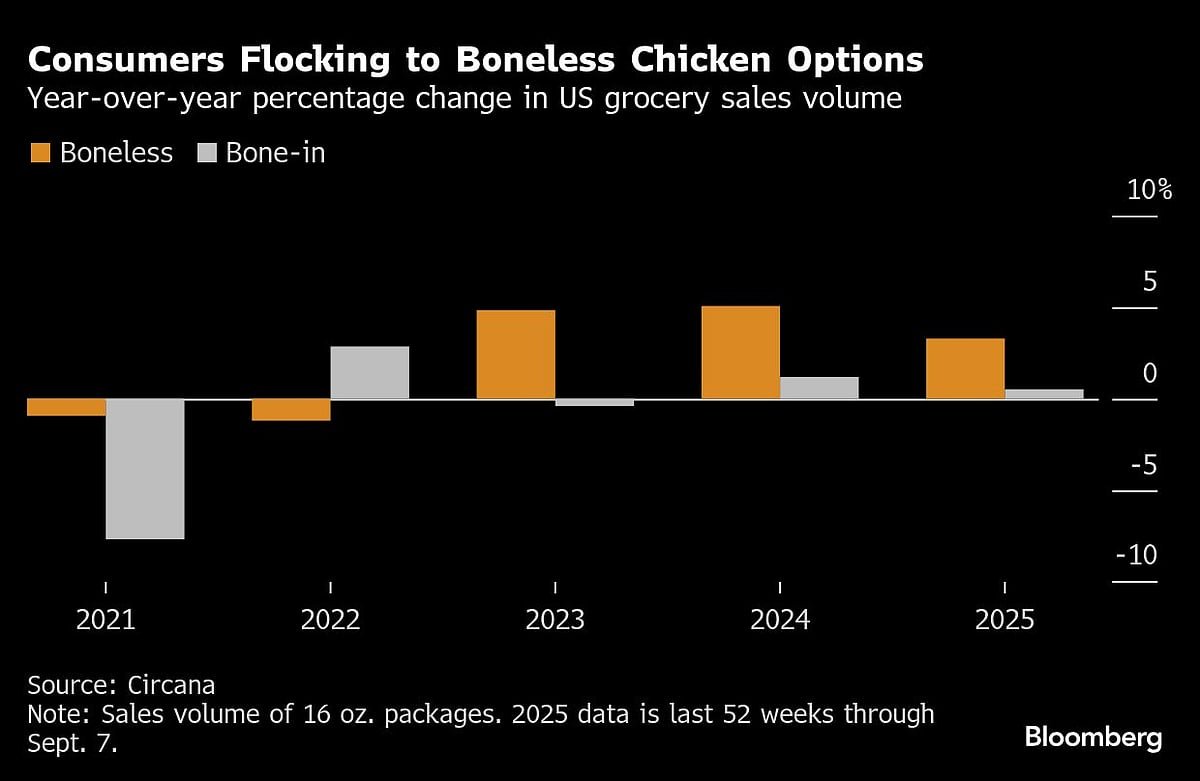

The problem for KFC, owned by Yum! Brands Inc., is in its bones. The 73-year-old brand’s focus on bone-in chicken — like its iconic red-and-white-striped bucket of fried drumsticks — has left it flailing among younger customers, who are obsessed with boneless white meat.

Since 2020, the amount of bone-in chicken sold at stores has fallen by 4%, while boneless is up 11%, according to Circana data.

So far, investors in Yum! Brands have been shielded from KFC’s underperformance, largely due to the success of another one of its restaurants, Taco Bell, which accounts for 82% of its US profits. The company’s shares are up 6% in 2025 and hit a record earlier in the year.

KFC is now looking to learn from the success of Taco Bell, well known for its limited menu drops and a steady run of new items, to boost its business. It’s also dropping prices, and has brought back its famous Colonel Sanders character — based on KFC’s founder — for advertisements alongside celebrity chef and The Bear actor Matty Matheson. It’s hoping the changes will help it regain a spot in the top three US chicken chains, after data from Technomic, which provides insights on food service and customer trends, showed it falling behind Raising Cane’s last year.

“When we became the number four player I think that was a huge call to action for the business,” Tan-Gillespie said. “Status quo is not going to be pretty for this brand.”

Going back in time, however, is part of the plan. KFC has already tapped into the resurgence of trends from the Y2K era by bringing back honey BBQ sauce and potato wedges, both staples of the chain’s 1990s menu. It previewed the wedges with a marketing campaign that included sending whole potatoes, stamped with the date of the relaunch, to a select group of food influencers. A single photo posted on X with the caption “HERE, DAMN.” — intended as an answer to the fans who’d been petitioning for the wedges to return — got almost 80 million views.

The company also dropped the price of its chicken sandwich to $3.99 from $5.49, despite an increase in the price of wholesale chicken.

“Especially for millennials and older generations, there’s a strong nostalgic connection,” said Tan-Gillespie. “We need to remind people what made us so great to begin with.”

Less likely to be captured by the trip down memory lane are members of Gen Z, who are the most frequent visitors to fast-food restaurants in general but were just 6% of KFC’s customer base through July this year, according to Numerator, a consumer data provider. When they eat at chicken chains, they favor tenders and nuggets — the boneless options that make up just a quarter of KFC’s menu.

KFC is working on updating its core menu to better reflect consumer tastes, said Tan-Gillespie — “How do we do buckets of tenders? What does a bucket for one look like, a bucket for two?” — but she declined to share any specific details or potential launch dates. KFC did briefly introduce what it called its “first new bucket in nearly a decade” during March Madness: a $7 meal that included tenders, mashed potato poppers and gravy dipping sauce.

This isn’t the first time KFC has tried a boneless identity shift. In 2013, the company ran a series of advertisements where customers chowed through a bucket of KFC, then freaked out — with increasing levels of intensity — that they’d eaten the bones. The reveal: they were actually eating the brand’s new pieces of boneless chicken.

Though the launch did well during it’s three-month run, it didn’t stick around. It was “perhaps a little ahead of its time,” in terms of what consumers wanted at the time, said Tan-Gillespie.

Whether the strategy succeeds this time round will be a key test for Chris Turner, the new chief executive officer of Yum! Brands, and his revamped KFC leadership team. Do they leave behind the bones to chase trends, potentially alienating existing customers in the process and with no guarantee they’ll be able to push back into a increasingly crowded market?

“The brand stands for a certain something, most famously, for chicken on the bone, for chicken by the bucket,” said Mark Kalinowski, president and CEO of Kalinowski Equity Research. “Coming out with other items that don’t fit that definition doesn’t necessarily change consumers’ thoughts and beliefs about what the KFC brand stands for.”

The irrelevance that Tan-Gillespie talks about is writ large under the blazing lights of Times Square, where flagship outlets of Raising Canes, Popeyes and Jollibee do steady business among tourists, and New York City office workers on their lunch breaks.

The closest KFC ever got to Times Square was just a few blocks up, in the theater district. But that location closed its doors during the pandemic, and now the nearest KFC is a tired-looking restaurant about a 20-minute walk south, sandwiched between an Irish pub and a hookah bar. Another Raising Cane’s sits just a few minutes walk away inside the recently renovated Penn Station cafeteria.

Since 2023, Yum! has closed about 300 KFC locations. Over the same period, it opened 412 new Taco Bell locations, according to company filings.

The Mexican-inspired franchise, whose bestsellers includes tacos and burritos, introduced crispy chicken last year and is bringing it back as a permanent menu item after the limited run sold out. Taco Bell’s chicken sales are up 50% in two years, and on track to double to $5 billion by 2030.

KFC US, meanwhile, hasn’t had a major capital injection in a decade, when Yum committed $185 million toward advertising and new equipment.

If you’re a Yum! executive, “KFC US is probably not where you direct a lot of your attention,” said Eric Gonzalez, KeyBanc Capital Markets analyst. “Doing that over long periods of time has its consequences.”

The lack of investment is noticeable to Precious McMillon, 34, who lives in Louisville, Kentucky, less than three hours drive northwest of the original KFC location. When she’s craving fried chicken, she prefers to go to a nearby Popeyes, where her order is usually chicken on the bone. A lot of that has to do with the in-store experience — KFC is “outdated, just not modernized,” said McMillon, 34.

“With the Popeyes that’s just right down the street, it’s a new store, and I feel like that makes a difference too,” she said.

Tan-Gillespie declined to give specific details of Yum!’s plans for investing in KFC US, but said there are some “really positive things happening on that front.”

A spinoff concept called Saucy by KFC, which focuses on chicken tenders with a lengthy list of dipping sauces, opened a single location in Orlando last year, with several more coming before the end of this year. On Yum!’s last earnings call, outgoing CEO David Gibbs said that a third of customers at the new store were under 30 years old. The company is due to report third-quarter earnings on Nov. 4.

A failure to successfully pivot would mean missing out on consumers’ seemingly insatiable taste for chicken. Over the last 10 years, US consumption of chicken has grown nearly 19%, compared to a 5.6% jump for beef, according to Brian Earnest, lead animal protein economist at CoBank. By 2030, Americans are expected to be eating about 105 pounds of the meat per person each year, data from the US Department of Agriculture show.

A key moment for the shift in preferences came in 2019 when Popeyes — long known for its bone-in fried offerings — launched its chicken sandwich, sparking an arms race for the best, most viral version. KFC was a third wheel, at best, as Chick-fil-A and Popeyes traded punches on social media and sold out of their products.

The craze lured burger chains McDonald’s, Wendy’s Co. and Burger King into the fray, and more than 60% of fast-food restaurants now offer a chicken sandwich, according to Dataessential.

KFC’s offering was just as good as the others, said analyst Kalinowski, but it wasn’t ready to fully commit to boneless meat. “A lot of franchisees are very happy to sell an awful lot of fried chicken on the bone,” he said.

. Read more on Business by NDTV Profit.